Automating Police Report Text: A Product Manager's View

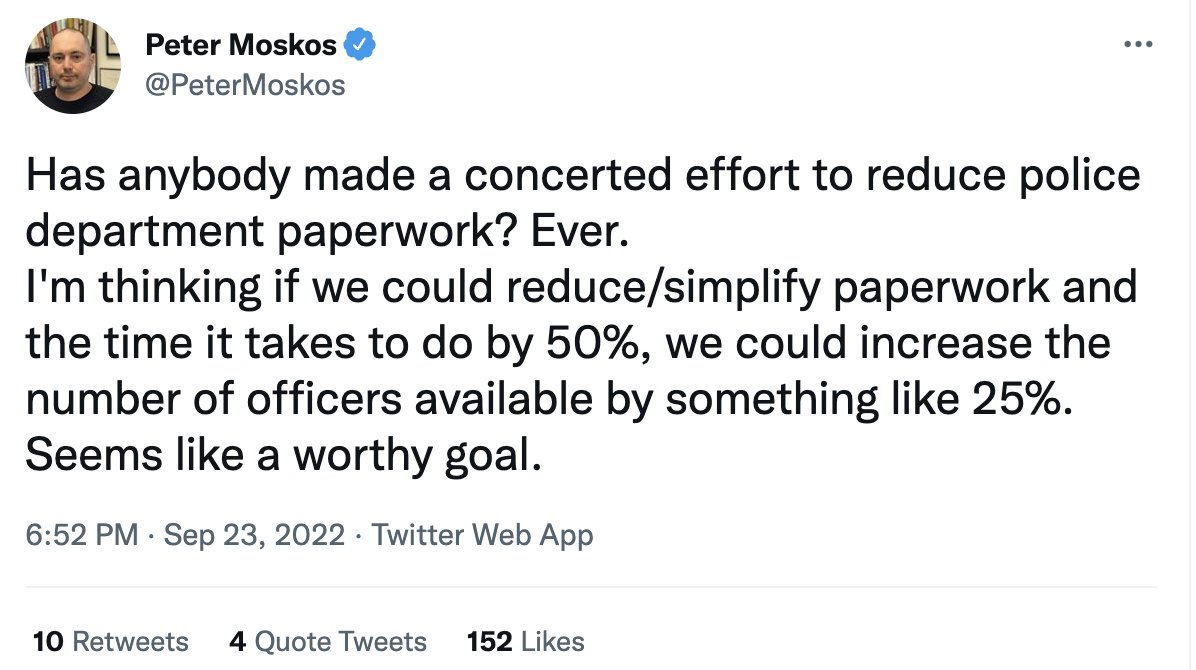

Recently on Twitter, Peter Moskos asked why paperwork could not be made easier for cops.

One Way We Automated Report Content at StreetCred

My former company, StreetCred - which as CEO I crashed into the side of a mountain - had some pretty fantastic law enforcement technology - not “for its time” but just, full stop great tech. Sure, it sucked, too. It is tech. But it was great because it removed toil, provided all the information needed to do the job without preaching about how the job should be done; it anticipated beautifully what the users would need to do next, and provided it - plus a way to easily break out of our expected workflow when the user wanted to make it different.

My failure was funding; the nearly 20 agencies running the tool all loved it, and reported low- to mid-double-digit percentage improvements in the closure rates of cases they worked with it.

So I think I am well-suited to talk about tech. No one should listen to me about money. If you’re thinking about making law enforcement technology, you should read this and learn from our toil, mistakes, and false-starts; by which I mean, our wisdom.

TL;DR

As experts in the processes of serving arrest warrants, we noticed that writing the narrative for police reports was a real slog. Cops would need to copy stuff from the warrant to the report - stuff that wasn’t easy for humans to copy, like driver license numbers, penal code entries, street addresses, descriptions… All the basic identifiers and references that computers can do faster than we can think of how to do it.

This is stupid, we thought, all that should just be automated.

Using the data we had and some very simple (tickboxes and dropdowns) original data entry in the field, StreetCred would generate arrest report narratives. This article describes what that was and how it worked.

A Sample Automated Report Narrative

On its face, it would seem really easy to generate the following sample text:

- On Sunday, 24 September 2022 I, Officer Joe Smith of the Springfield Police Department (Shield #892), on duty and assigned to the Warrants detail, drove in marked unit 34 to 123 Any Lane, Apartment 3723, Springfield, 12345, where I had reasonable suspicion that I would locate JONES, OLIVER WENDALL, white male, DOB 01/22/1997, brown hair, brown eyes, State Driver License 18225173, and for whom on 30 March 2022 Judge Doe of the Springfield Municipal Court had issued an arrest warrant on a charge of Transportation Code 550.022. ACCIDENT INVOLVING DAMAGE TO VEHICLE, Failure to Remain at The Scene of an Accident. Prior to entry, I confirmed the validity of the arrest warrant with Dispatch. I located JONES at the above address, informed him of the charges, and placed him under arrest. I handcuffed JONES, double-locking the handcuffs, then patted JONES down for weapons. No weapons were discovered during this pat-down. I placed JONES in marked unit 34, seat-belted JONES, and then transported JONES to the Springfield Municipal Jail. I booked JONES into the Jail.

Here’s another version, with a female prisoner:

- On Sunday, 24 September 2022 I, Officer Joe Smith of the Springfield Police Department (Shield #892), on duty and assigned to the Warrants detail, drove in marked unit 34 to 123 Any Lane, Apartment 3723, Springfield, 12345, where I had reasonable suspicion that I would locate JONES, SARAH JANE, white female, DOB 01/22/1997, brown hair, brown eyes, State Driver License 18225173, and for whom on 30 March 2022 Judge Doe of the Springfield Municipal Court had issued an arrest warrant on a charge of Transportation Code 550.022. ACCIDENT INVOLVING DAMAGE TO VEHICLE, Failure to Remain at The Scene of an Accident. Prior to entry, I confirmed the validity of the arrest warrant with Dispatch. I located JONES at the above address, informed her of the charges, and placed her under arrest. I handcuffed JONES, double-locking the handcuffs, then patted JONES down for weapons. No weapons were discovered during this pat-down. I placed JONES in marked unit 34, seat-belted JONES, informed dispatch my starting mileage an activated my vehicle's interior video camera and recording system, transported JONES to the Springfield Municipal Jail, informed dispatch my ending mileage and deactivated my vehicle's Interior video camera and recording system. I booked JONES into the Jail.

The rest of this article is how we did it, and why it is not easy at all.

What StreetCred Did

It aggregated records from multiple local, county, state, and federal systems, and then algorithmically analyzed the data to help, for example, determine the current location of wanted fugitives and, more important, analyze police interaction with civilians over time to determine which officers were behaving poorly. By “algorithmically analyzed” I mean that this was not Machine Learning, but it was orderly: a series of nested if/then/else statements.

This aggregation of data from heterogeneous systems required many things that many LE tech vendors are unwilling or unable to do:

- Locate the data within the correct system. Police records are *always* in a different place from where you'd expect. Sometimes they are not even in police systems, they're in the court system. As cops ourselves, we knew which questions to ask, and we didn't have commercial bias telling us not to deal, for example, with anything from Vendor X.

- Export, ingest, aggregate, normalize, de-duplicate, index, correlate. Just having the data is not the answer, it needs to be usable.

- Let the data tell the story. Law enforcement is inundated and overwhelmed with data. We converted the data to information, the information to intelligence. What about the data do I need to know, and when? Most of our algorithm was *disqualifying* inclusion - throwing data away. For example, if you have a corpus of 160,000 active warrants, the first question should be "How many of the people in this corpus have died?" and then removing all those warrants from the system. Turned out it was routinely 1%-2% of the total. The software correlated by asking of the data about 75 of these kinds of questions, then presenting the results in an ordered list sorted however you'd like.

Finding The Data

I said our police expertise gave us insight into police data sprawl. As an example, consider the police record of a vehicle stop that led to a probable-cause search of the vehicle, that led to an arrest, and after the person was released, an arrest warrant was issued on more complex charges. An every day thing.

But, as examples:

- The data for the car stop is probably in the Computer Aided Dispatch system.

- The data that there was a search is probably in the CAD, plus perhaps in the Records Management System.

- The data of the fruits of the search will be referred to in the RMS, and stored in the Evidence Management System.

- The data about the arrest itself will be in the CAD and the arrest report in the RMS, the booking and jail data in the Jail Records Management System.

- The data about what was taken from the arrestee on Booking and subsequent to search would be in the Evidence Management System.

- The data about the arrest warrant will be in the Court Records Management System.

- The arrest warrant itself will be maintained in a paper copy in the court filing system.

Knowing where to find these systems - often (in smaller agencies) stored in different non-integrated systems made by different manufacturers is just half the battle. Then one must access the data within - legally, politically, organizationally, technically. We chose inter-operability over the much more complicated, expensive, and time consuming “integration”; interoperable meant we ask these systems regularly for updates, and update our records separately, continuing to treat the original system as the One Source of Truth. That meant we could not write our findings back. Their loss.

Opening Our Data

So as not to be part of the larger problem ourselves, we made a decision at the very beginning to open our data:

- All our data was in standard formats (e.g., JSON);

- All our data was freely available to the client agency without our involvement;

- Our code itself was open source;

- All our data would be available at no cost to other manufacturers;

- We would at no cost integrate (accept input from) any CJIS compliant LE vendor.

Report Writing Automation: Use The Data We Have

With respect to the fugitive, we had the following information:

- Warrant number;

- Criminal charges;

- Fugitive name, address, city, state, ZIP code, driver license number, DL state, height, weight, eyes, race, sex, date of birth, photo;

- Fugitive vehicle year, make, model, color, VIN, license plate number, cost, seller name, insurer, registration date, photo

- Date of the warrant’s signing

With respect to the officer, we knew:

- Officer’s name, sex, rank, badge number;

With respect to the agency, we knew:

- Agency name and address;

- Agency protocols and processes regarding arrest, handcuffing, prisoner transport, and jail procedures.

Putting This Together

Data we knew we needed based on agency policy and procedure - this is an example, it changed per agency - included:

- What police car is the transporting officer driving?

- Arrestees shall be handcuffed, the handcuffs double-locked, patted down for weapons;

- They shall be placed in a transport vehicle, seat-belted;

- If a male officer is transporting a female prisoner, the interior vehicle cameras shall be activated, and dispatch notified of the time transport begins, the starting mileage, and the time transport ends and the ending mileage.

With the information I have just given you, our system could then produce a narrative provided that the officer enters the vehicle number, and ticks the following boxes:

- Did you handcuff the fugitive?

- Did you double-lock the handcuffs?

- Did you pat down the fugitive for weapons?

- Did you locate any weapon(s) during the pat-down?

- Did you place the fugitive into the transport vehicle?

- Did you fasten the fugitive’s seat belt?

- Did you transport the fugitive to the city jail?

- Did you book them in to the jail?

The system knew the sex of the officer and the fugitive, so if the former was male and the latter female:

- Did you activate the internal vehicle video?

- Did you report to dispatch the time and mileage at the start of transport ?

- Did you report to dispatch the time and mileage at the conclusion of transport?

How This Worked

The officer would use a page in the StreetCred system to get all the information available on a particular fugitive. When they made an arrest, they would click the Generate Arrest Narrative button, and the dialogue would guide them through the necessary tickbox questions, situational to the sex of the officer and the fugitive. The officer would enter the requested data and click, “Generate”, and the system would then present the text of the report. Because StreetCred was required to run over a persistent VPN tunnel, it would also simultaneously send an internal agency email to the officer (to avoid sending unencrypted information over the public Internet). The officer would then copy the narrative text and paste it into their arrest report.

What Was The Pushback?

Initially there were questions: is the machine writing this, or is the cop? Ultimately in conversations with city attorneys, it became clear that the officer was in fact writing this narrative because the only verbiage that was being created by StreetCred was created as a direct result of the officer’s actions: the officer selects the fugitive of interest, the officer confirms the information within StreetCred and validates the warrant with Dispatch, and the officer initiates the arrest narrative process and enters in the field the information that is unique to the arrest. There is, they and we argued, no difference between the officer holding the arrest warrant and copying from it the fugitive’s height, weight, and driver license information, and StreetCred copying that data for the officer.

What Was The Reaction?

Hey, I’d like to remove totally unnecessary toil from your work with no downside, is that OK with you?

How Did You Do It?

The attentive reader will note that the data simply must be aggregated from a range of sources. For example, we got the warrant data from the court record management system, the vehicle information and fugitive driver license photograph from the state DMV, lots of the situational awareness information (like gang members and sex offenders near the fugitive’s house) from the agency record management systems, current felony information from the National Crime Information Center and regional (misdemeeanor) wants and warrants from a regional warrant databases, death information from the Social Security Death Index, jail information from an internal proprietary system that queried the jails of all the surrounding counties, etc.

There were some records we needed to get that helped us locate people that were non-law enforcement. For example, if the driver license said Mr. Jones lives at 123 Any Lane, are there any municipal construction permits with that name at that address? Is he the owner of the building? Are any pets registered to him at that address? Any hunting licenses issued to him at that address? Etc. These came from municipal, county, and state records, and other agencies.

In each case, we would find the easiest way to export raw data from the systems, normalize and ingest that. This often required agreements (or, sometimes, non-agreements in which the vendor would not approve but told us they wouldn’t object). Often this required writing scripts in COBOL or other languages to interact with the system’s internal workings.

Why Don’t More People Do This?

Think of the level of intricate subject matter expertise described here. First, we needed to understand that the data existed. Second, we needed to figure out where it was. Third, we needed to get the permission of that agency overseeing the desired data-set to allow it to be used for the purpose. Then we needed to get the permission of the vendor making the system that stored the data. Then we needed to reverse engineer the process of getting the data out of whatever weird, proprietary, non-relational flat-file or relational database it’s in, normalize it, then ingest it and de-moronize it to place it in an open standard format. Finally, we got to process the data.

That’s a lot of expertise, a lot of horse-trading, and a lot of hard work, and most vendors won’t do it and most chiefs, judges, and city administrators and attorneys won’t allow it.

When you ask yourself why we can’t “just” automate report writing, this should give you some insights into some of the answers.