A Bird's Eye View

There is an article looking at police killings in 2015 published in Criminology & Public Policy by Nix, Campbell, Byers, and Alpert, and it points out a couple of things that are noteworthy.

I think, with some distance from the project, and after speaking a lot with D. Brian Burghart (whose Fatal Encounters was actually the first fully-fledged project to actually count police killings), and review of the 2016 data from Fatal Encounters, Washington Post, Guardian, and Killed By Police, that I have come to a conclusion.

It is important to remember why we started counting these deaths. It was not (though The Washington Post and Black Lives Matter may disagree) to come up with a tally of how many people die after police encounters. I’ve said many times that the goal of policing is not zero deaths – anyone saying otherwise has some cut-rate consulting to sell you.

Some people truly need to be killed: those like Denzel Brown, who was in the process of kidnapping two children, aged four and six, in their parents’ vehicle, and refusing to stop, for example. Those killing without mercy unarmed people at a military recruiting station, like Mohammad Abdulazeez. Or those who are an escaped prisoner, motorcycle-and-car-thief, carjacking, female-assaulting, meth-head junkie on a rampage, like Shane Gormley.

There are, in fact, thousands of those situations for every Walter Scott – a man running from an officer when the officer shot Scott multiple times in the back, killing him. Thousands to one.

Every year, in fact, according to the data at (and conversations with those who run) Fatal Encounters, something like 1,500 Americans die after a confrontation with police. Every year, about 1,400 of these decedents were obviously, uncontroversially in the midst of a deadly attack (against the police or a third party) in the manner of Brown or Abdulazeez, or Gormley; or who were in the process of a drug overdose or physical health emergency when they died.

After investigation, another 80 to 85 cases shake out, and evidence ultimately emerges that show the officers may not have acted clearly in the best possible manner, but neither was their behavior illegal or even wrong: perhaps they panicked, or perhaps they overestimated the threat.

This leaves us, each and every year, with somewhere between 15 to 20 cases of what appears to be actual malfeasance by officers, actual bad intent.

That’s not a “good” or a “bad” number, it’s just what it is. My analysis is that, in a nation of 320 million, in which there are 40 million face-to-face interactions between citizens and the 800,000 police, from 18,000 agencies, who protect the populace, even 100 questionable uses of deadly force is, while of course tragic for the 100 and their loved-ones, not an epidemic, or an indication of systemic abuse of police power.

And determining whether it is systemic is the point of the counting. It’s not just the raw number. It’s the why that matters. We must count to ensure that there is no systemic bad intent; no systemic trend. We must count and include the context.

In A Bird’s Eye View of Civilians Killed by Police in 2015, Nix, Campbell, Byers, and Alpert state that, after their analysis of the Washington Post data of officer shootings (a little more than half of those who die each year are shot to death by police), “The results indicated civilians from “other” minority groups were significantly more likely than Whites to have not been attacking the officer(s) or other civilians and that Black civilians were more than twice as likely as White civilians to have been unarmed.”

Note, that by claiming that “Black civilians were more than twice as likely as White civilians to have been unarmed,” an uneducated reader might conclude that this means that the officers were twice as likely to shoot a non-dangerous black person. That’s not what the finding is. It’s highly nuanced, and while I suspect the authors did not mean to confuse, some may be confused – as I have pointed out elsewhere, “unarmed” does not mean “not dangerous.”

The authors use Washington Post reporters to code the data as to whether the decedent was in the midst of an attack at the time of their death. I have some challenges with that that I raised with the authors, but Peter Moskos handles this much better than I can in his Cop In The Hood blogpost on the topic.

In that post Moskos discusses how the implicit bias that may have led cops to select unfairly almost twice as many non-attacking black people as white people in 2015 seems, by looking at the WaPo data in 2016, to have literally reversed itself – there is almost twice as much likelihood that officers will kill a white person than a black person. Adding the two years together, of course, gives us an average of the two, or a neutral implicit bias.

Oh, dear.

That jibes with what we found from 2015, but I cannot help but wonder why we didn’t pick up on the implicit bias issue on the 2015 data.

In part, it is likely that one reason is because the researchers here use only shooting data (The Washington Post counted 93 unarmed people in 2015, whereas we counted 83 that met our criteria), while we use all causes of death (our total was 153 unarmed people). Since 83 of 153 people (54%) were fatally shot, 70 (46%) died by some other means. Now, a lot of those “other means” included things like, “taking more methamphetamine than we would have thought possible, jumping through windows, fighting cars, bystanders, TASERs, and officers,” and then dying of heart failure – so these extras probably ameliorated any “implicit bias” effect that may have been present in the data of people shot to death by police.

In part (and I know I said that Moskos covered this, but here goes), I suspect that our team – myself, Ben Singleton and Ed Flosi – with a combined more than 50 years of use-of-deadly-force expertise and law enforcement experience, and our peer review group, with more than 150 years of combined use-of-deadly-force expertise and law enforcement experience – are just plain better at coding the data using the Graham and Tennessee v Garner standards than are the reporters at the Washington Post. Nothing against them, it’s just that they are reporters, relying for facts on other reporters, and to my knowledge they have little or no relevant experience or training to understand the nuance of what actually comprises an attack.

Put plainly, I don’t see anyone accounting for the implicit bias present among the team doing the coding at The Washington Post.

But Moskos rightly points out that the coding issues almost certainly come down to a very few cases that we can really argue about, and again, we end up talking about the very small number of cases overall - that brings me back to my main observation: There are fewer than 100 people a year killed in truly controversial events. Ultimately, I would say that the total number of actually, genuinely unjustified killings by police each year is probably in the area of 15 to 20.

Again, while this is, of course tragic for the 15 to 20 and their loved-ones, it is just not systemically significant in terms of how we as a nation are policed. Plainly put, these deaths are not part of any “pattern and practice” of abuse: they are each isolated incidents, geographically and culturally far from one another.

Finally, it is worth widening the aperture from the simple analysis of “the moment of use-of-deadly-force,” which is the orthodox method of consideration of use-of-deadly-force, and looking at the context of how the cops got to each incident to begin with.

How The Cops Got There

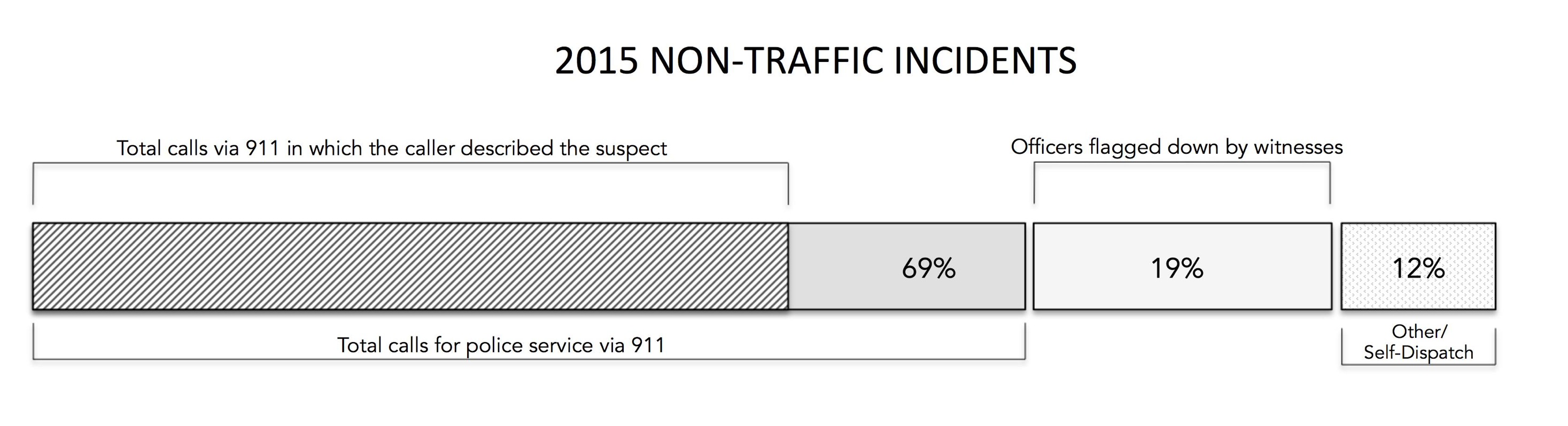

The PKIC data reveal that it is citizens who initiate most of the 72% of deadly encounters that don’t begin with traffic stops. In 88% of those 72% of cases, citizens — and not the police — initiated the encounter by asking an officer for help.

In our book, we depicted this graphically:

Put another way, when considering the 72% of cases in the database that did not start with traffic stops, the number of minorities contacted by police, and proportion of black people to white people to Hispanics, is not relevant to the question of officer targeting of minorities. This is because in nine out of ten cases, it was a member of the community and not a police officer who selected the person to be contacted.

Media narratives (like those of the Washington Post) that state the police are more likely to target black people in deadly encounters are, statistically speaking, demonstrably wrong.

911 Callers Describe the Suspects Officers Target

Moreover, in nearly 80% of the emergency calls, the caller specifically identified or otherwise described the suspect who ultimately died. There were no false identifications.

In the vast majority of the 110 non-traffic incidents in which people died (of 153 total), race was not a factor in the commencement of the incident.

We therefore know the following:

The police did not select most of the people they confronted;

Just about 70% of unarmed people who died at the hands of police were reported to the police by citizens as being a danger to the community, rather than selected by police for attention;

Even When The Police Select, The Racial Composition Is The Same

The racial composition of the group reported to the police by the community does not differ significantly from the racial composition of the group the police self-dispatched.

Most of Those Killed Were Engaged In Deadly Activities...

As I said above, the overwhelming majority of those ultimately killed by police (even, though they reckoned lower than we did, by the reckoning of the Post - there’s that coding issue again) were themselves engaging in behavior that was criminal (which brought the police to the scene), and posing direct threats to law enforcement or other civilians (which most often precipitated the use of force);

...But We Still Don’t Know If Police Treat Races Differently Once Contact Is Made

Note that neither our work, nor (sadly) the work of Nix et al – given the further analysis by Moskos of the 2016 data – answer the question of whether the police treat white people differently once an event begins – this is a separate question that must be answered using a much wider array of contextual data. We have, all of us, called for more and better data.

Stop Using Population

Finally, I was very happy to see researchers in a peer-reviewed journal finally put the kibosh on the repeated habit of reporters to say the “police are n times more likely to kill black males,” than they are to kill other people. There’s so much wrong with that, as I’ve pointed out on television, radio and in print, at varying levels of level calmness, furious anger, overt and thundering hysteria and meek surrender over the past year and a half that I was beginning to question whether anyone would ever come back to it.

Here, Nix et al comment: “We caution against using population as a benchmark because it does not account for each groups’ representation in a variety of more relevant measures, including police–civilian interactions and crime.”

For those unfamiliar with the language of academia, the researchers just called these reporters dopes. I concur.

“The use of self-report data in criminological research,” the researchers continue, “has resulted in the finding that Black citizens offend at higher rates (Blumstein, Cohen, Roth, and Visher, 1986; Loeber et al., 2015) and are overrepresented in citizen complaints/calls for service (Engel, Smith, and Cullen, 2012), police stops (Novak, 2004), and arrests (Brame, Bushway, Paternoster, and Turner, 2014; Kochel, Wilson, and Mastrofski, 2011).”

That jibes not just with our work on In Context, and other work to understand these phenomena. It leads me to conclude that reporters who continue to go with the population-derived numbers in the face of smart people telling them that those numbers are flatly wrong, are either monumentally sophomoric, or unforgivably hypocritical and misleading.