Making Police Data Open: Use of Force & Complaints in Context

Last year, Indianapolis Police Department officers working the middle shift in the Eastern District received at least twice as many complaints of rudeness and hostility than officers on almost any other shift, in any other area. These are a combination of complaints for things like, "Rude, demeaning, or affronting gestures," "Rude, discourteous, or insulting language," "Rude, demeaning, or affronting language," "Indecent or lewd language," and similar charges. Complaints are mapped to the regulations that IMPD officers must follow, hence the slightly variant complaint descriptions about basically the same thing: discourtesy.And 63% of those complaints came from white people.

The second highest numbers of complaints of rudeness and hostility were leveled against officers on IPD's Eastern District late shift. But 65% of those complaints were made by black people.

I know this because I was able to download Indianapolis Police civilian complaint data from Project Comport, brought to us by Code for America's Team Indy, and the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department. Comport is a tool for law enforcement agencies to open their data and be accountable to their citizens.

Professor Peter Moskos and I recently wrote that, "behind the dry statistics and chilling tallies, there are human beings in each of these cases. Our point was that when people look at data about criminal justice — from police-involved killings, to use of force, to complaints of officer rudeness — through ideological goggles, they tend to view it from an extreme. And whether that means they think all cops are racist, or that whatever cops feel they have to do is justified, ideologues have stopped listening to constructive criticism.

Open data fuels great constructive criticism, because it lets us make targeted constructive criticism that is based on fact, not narrative.

With Comport, law enforcement agencies can plug in existing internal affairs data, add contextual information about policies and programs, and quickly create an open data site. That fuels conversation, and most important, fosters openness.

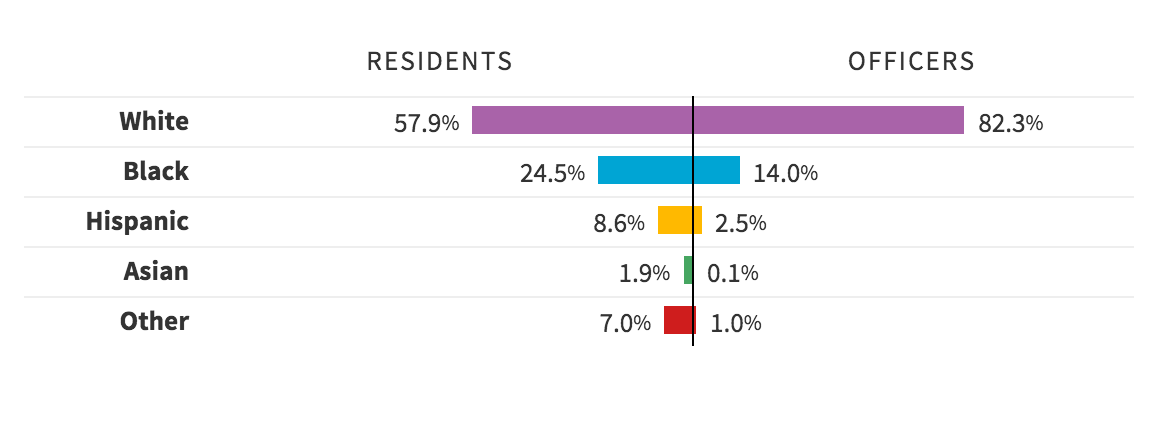

Comport doesn't ask or answer all the questions I am talking about here. But it does serve up beautiful and easy to understand visualizations of questions that have been asked by the community, about race, types of force, types of complaints, and outcomes. And it lets you download all the data yourself, free, so that you can do your own research — and double-check Comport's.

Comport doesn't ask or answer all the questions I am talking about here. But it does serve up beautiful and easy to understand visualizations of questions that have been asked by the community, about race, types of force, types of complaints, and outcomes. And it lets you download all the data yourself, free, so that you can do your own research — and double-check Comport's.

When you have good, open data, your community can ask questions. Like drilling past race, into officer cohorts. On the late shift in Indy's Eastern District, more than half those discourtesy complaints were on officers under age 40, and half of them had been on the job for less than 6 years.

Good questions let you seek patterns. Good questions of good data lets you find them.

For example, Indy's lowest median household incomes, and highest rates of poverty, are concentrated in neighborhoods up to four miles east and up to three miles southeast of Downtown Indianapolis. So what is it about that eastern district that makes police rude to more white people during the day and more black people at night?

Does its population change from day to night? It sure does in lots of communities, especially in larger cities, in areas where people work on the day shift.

Does its population change from day to night? It sure does in lots of communities, especially in larger cities, in areas where people work on the day shift.

Or does race have less to do with these kinds of complaints than other factors, like shift supervision, or the officers on duty, or crime rates, or…

Again, Comport doesn't go this deeply, but it gives you a great starting point.

Good data lets you ask questions.

Recently I wrote in the Washington Post about how statistics on traffic stops and policing could look like racist policing — black women in an area were being charged $204 more per stop than white women — but in fact were based not on policing, but on a fine structure put into place by ill-planned legislative attempts to reduce drunk driving. I suggested that, without this data, the police department would not be able to effectively lobby on behalf of its community, something it is now able to do.

If we didn't have the data, we wouldn't have ever seen this issue.

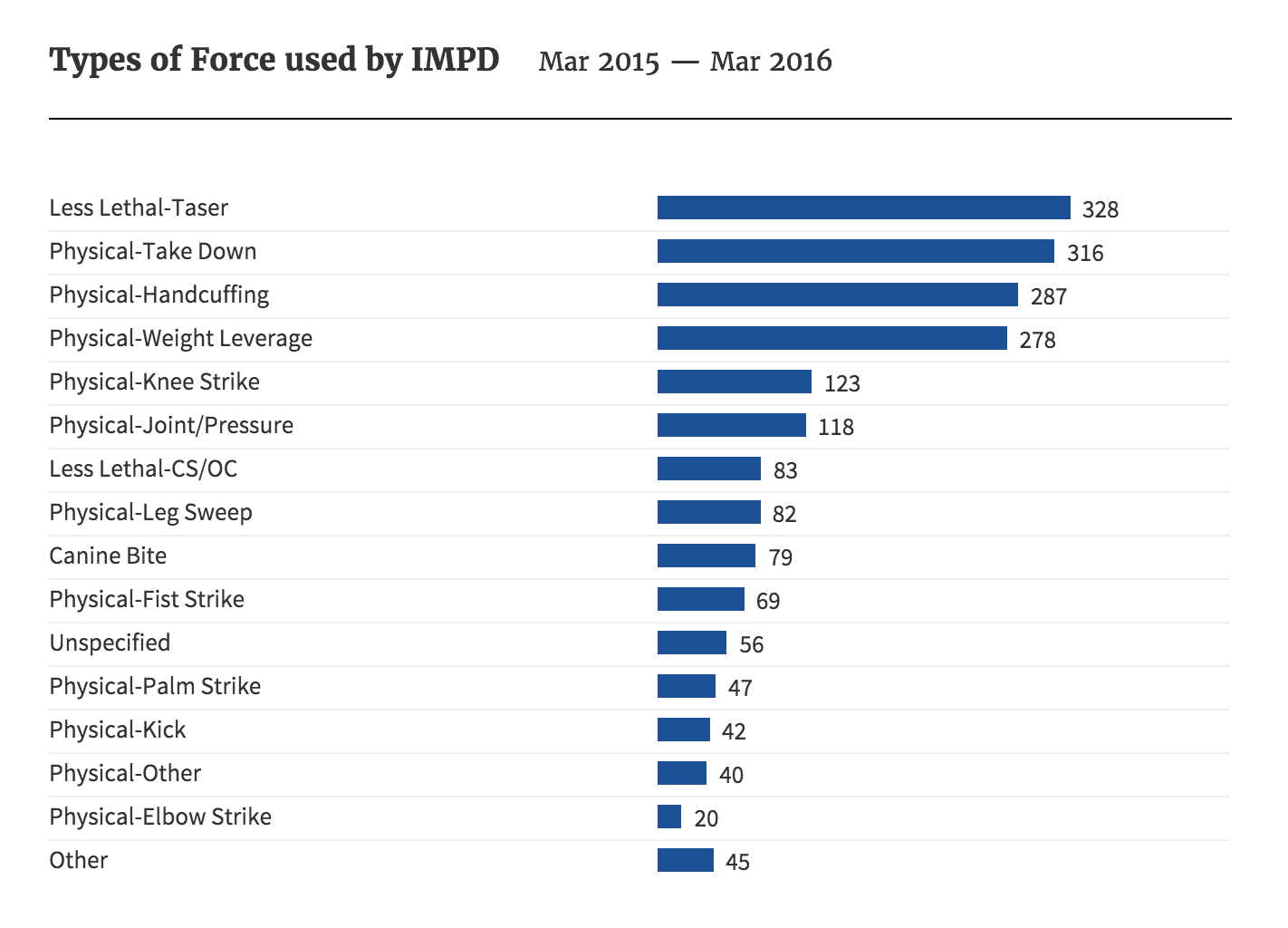

Sometimes, open data like Indy's can just serve to confirm the reasonably obvious: it might make sense that 61% of officers who use a knee-strike are under the age of 37, or 68% of officers using a palm strike are older than 37.

Sometimes, there are oddities: department-wide, 54% of TASER deployments are made by officers older than 37. And while 53% of TASER deployments are made by officers with less than nine years of service, hairbags (veteran officers) as a group are the single biggest users of TASERS — 27% of all deployments were by officers with more than 14 years on the job.

The biggest group, that is, except in the Eastern District! Because back there, on the middle shift (which, with 30 deployments in 2015, had the highest rate of deployment in the department), fully 90% of the deployments — nine in ten — were by officers with less than nine years of service, and half were by rookies — those under 6 years on the job.

Twenty-seven of those 30 daytime Eastern District TASER deployments were against black citizens. That's 90%. So, does the citizen's race make a difference in this case? Good data lets you ask questions. Good data lets you overlay other good data, to get answers. So let's overlay data on poverty; on general crime rates, on car thefts, and aggravated assaults, and sexual assaults, and homicide. And on school lunch programs, and parks.

Let's find the answer.

Let's use the data to get to the bottom of these issues, so that we're not just shouting about them, but we're also doing something to change them. Let's not just yell about "bad cops," let's use the data to find out which cops are repeat offenders, and get them trained or get them fired.

And let's start looking at connections between possibly related issues — such as discourtesy complaints and use of force, or discourtesy complaints and shift supervisors — to see if we can help discover new ways to find cops who may be heading down the wrong path, and train them up to set them back on the right one.

I urge you to go and get the data — on use of force, on complaints, and on officer-involved shootings.

As you use it, consider that the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department has taken a risk that should be applauded: they are going the extra step to make it easier to get data that, in careless hands can be used to make the department look bad. This is so important to recognize: when police departments do the right thing, and do it right, we really have to recognize that.