Some More Thoughts On Body-Worn Cameras

On April 1, USAToday ran an opinion piece Rachel Levinson-Waldman and I wrote about police body cameras. The main point of the article was not necessarily that video can't be relied on as an across-the-board solution to life's problems - that question was beautifully handled in a New York Times interactive feature based on the work by Seth Stoughton.

Instead, our piece was about the fact that body-worn cameras can solve many problems, just not at once. That the real issue with cameras wasn't buying them, but rather writing the policies that help officers and prosecutors use the video produced when officers wear the cameras in a manner that can accomplish measurable progress towards a stated goal.

Here's my favorite section:

If police accountability were the only goal, release of videos could be required so citizens and journalists could play an oversight role. They might require officers to write up their reports before viewing video to ensure that their recollection isn’t tainted. And they would likely call for videos to be kept for as long as civilians have to file a complaint – often several years.

But accountability is not the only objective. How law enforcement uses and manages cameras might look very different if policymakers instead decide to prioritize collection of evidence for criminal cases. Defense attorneys for years have looked to video when challenging DWI cases, and both prosecutors and defense lawyers increasingly see body camera video as a rich source of evidence.

With this aim in mind, policymakers might limit public and press access to videos, while encouraging officers to view videos before writing their reports to incorporate as much detail as possible, an approach that most departments take (but many civil rights groups oppose).

Anyway, I hope you like the piece - Rachel and I don't agree on everything, and in fact we approach from opposite ends of the spectrum politically, but I like to think I am as reasonable and pragmatic as she, and I am truly honored that we can collaborate on this and other issues.

By the way, back to Stoughton's excellent piece. It is a test of sorts: you're shown several videos and asked questions. First, of course, you're asked some of your feelings about police in general. After you answer the questions, you can look at different videos that give you different perspectives of the scene you just saw. then you can see whether your impressions from the first video were correct. And most interestingly, how your impressions map to the answers you gave about your attitudes towards police.

I have one criticism of the presentation. The work itself is wonderful and necessary, and I believe that the Times covering it the way they did is ultimately great because it brought to a mainstream audience analysis about how much trust we might rightfully put into our viewing of videos. But the presentation might leave lay-people to presume that snippets of video are ever or even often viewed with NO context. In fact, the overwhelming majority of the time, that is simply not the case.

In fact, the only time that would be the case would be when a solo officer was killed and all that remains is the video. In such a case, these clever scenarios would not be remotely relevant (I won't say why, because I want you to read the article and take the tests). But I will say this: for every video we have, we have an officer's story behind it, and that story is backed up with metadata and other testimony.

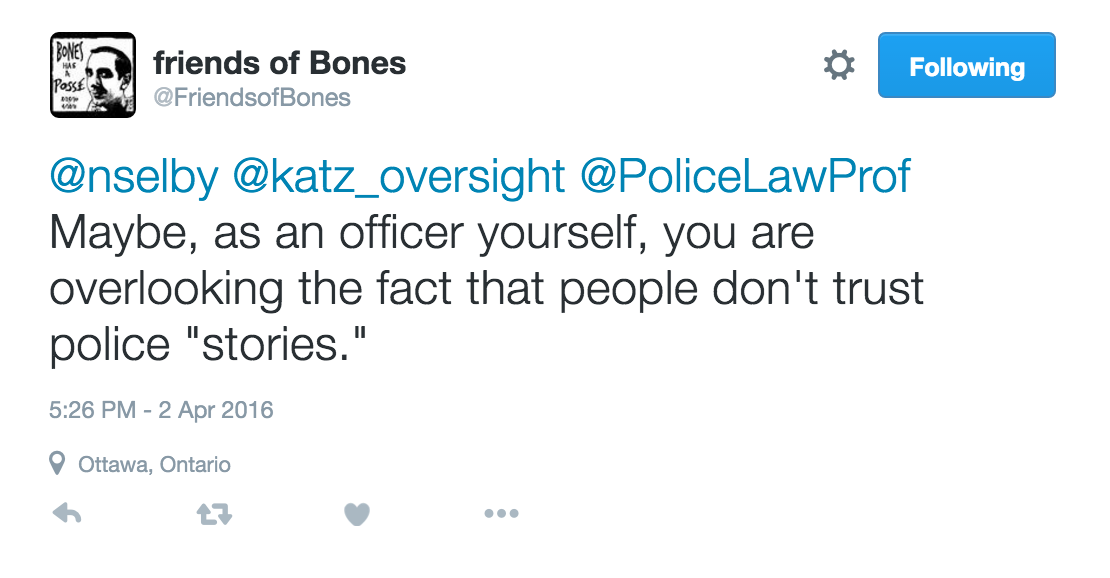

When I mentioned that on Twitter in a conversion with Stoughton and police citizen-oversight professional Walter Katz, someone else (a user with whom I engage quasi-regularly in respectful conversation and sometimes debate) chimed in with an important nuance to that statement:

That is very true, but implies that I said the police should be believed. Regardless of whom is believed, the police account of what happened, metadata - like Computer Aided Dispatch and police records, radio calls, plus witness accounts and complaint data - all can be used to contextualize what is being viewed and whether what is being viewed jibes with the account and the metadata.

So while Stoughton's experiment is fascinating, and provides really excellent information on inherent bias, I think its presentation and ediorialization in the Times may have left people with the impression that it has a more directly relevant message with respect to body-worn video than it actually does. The question is not whether video should be trusted, it is how video can be implemented and analyzed in the most useful way to meet stated goals. As a society all these kinds of points must be taken into account in order to create frameworks in which video can be another tool in the hands of police, administrators, oversight professionals, prosecutors, journalists and activists.