Police Body Cameras: The Best Thinking So Far

For the past year and a half, Americans have been very interested in police body cameras - most specifically, why more cops don't have them. As I go around the country having conversations with police agencies and citizens, they're often as shocked to hear that, in 2013, while 81% of police officers have TASERs, only about a third (32%) have body camerasBJS NCJ 248767, Dr. Brian A. Reaves, July 7, 2015.

You'd probably expect the body-worn video camera adoption number to have increased to more than 33% of police agencies by this year. So, it's an interesting data-point that, according to StreetCred Police Killings in Context data, video was only available in 26% of cases in which a police officer killed an unarmed civilian. And while most people know that witness video was crucial to show officers were not truthful with investigators in two cases, most don't know that in two other 2015 cases video fully exonerated the officers.

What is most surprising is that, in all four of these cases, video was photographed by bystanders or surveillance cameras, not police video.

About a year and a half ago I wrote a fairly long blog post about the main barriers to police video, which I considered to be generally grouped in the areas of Standards & Guidance, Bandwidth & Access Control, Integrity, Storage & Retention, and funding. Now Professor Elizabeth Joh has written the first draft of what will certainly become a truly great paper on the subjectJoh, Elizabeth. "Beyond Surveillance: Data Control and Body Cameras." Surveillance and Society, 9 Mar. 2016.. I figured that, since she did that, I'd riff on some of my thoughts about some of her thoughts.

Whaddaya think?

Who controls the data?

Joh focuses her paper on the important questions around the data - how it is created, processed, and stored. As a part of this she refers briefly to the physical form factor of the device, including this brilliant and insightful observation:

“The very design of a police body camera can influence the resulting data. Seemingly mundane questions of equipment design and cost can shape the information produced.”

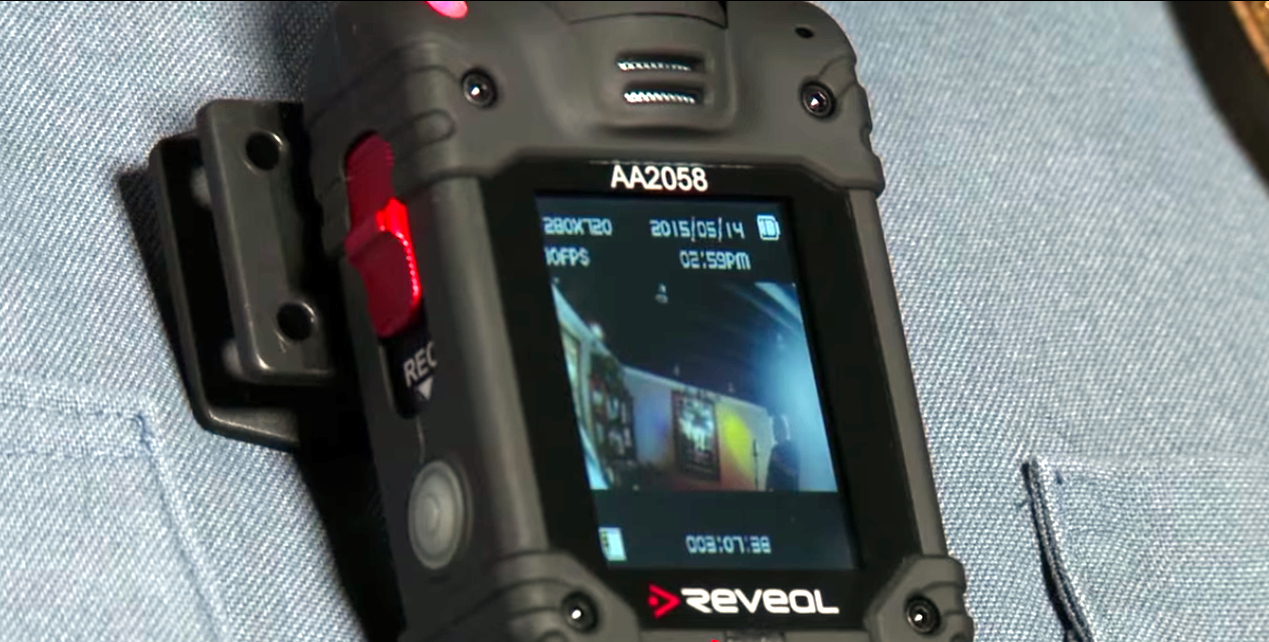

This is a huge issue that doesn't get considered that often, and is really at odds with the way American policing tends to buy equipment. US cops like to buy the same equipment for everyone, and that is limiting, especially when, sometimes, the kind of camera that might be right for many officers (the Reveal camera here, developed in the UK with a UK design sensibility based primarily around UK  societal privacy expectations) might be great for a range of activities in which it's fine to let people know you are recording. But in many US use-cases, the sight of oneself on video might very well be provocative to those being policed.

societal privacy expectations) might be great for a range of activities in which it's fine to let people know you are recording. But in many US use-cases, the sight of oneself on video might very well be provocative to those being policed.

Paying close attention to the physical form factor is also important when it comes to a range of non-obvious police activities and assignments. And, as Joh notes, with just two vendorsTASER International and VieVu dominating the space, this has a stifling effect on choice here. I don't expect to solve this issue, but I note that Joh is absolutely on to something that is the center of conversations throughout the American policing community.

When Should Officers Record?

Another really important aspect of this is when officers should record. The fact that so few of the killings by police of the unarmed in 2015 were recorded speaks to this, and as I've written before,

“The ‘CSI effect’ on juries informs my prediction that, three years from now, if video is unavailable, the police will be disbelieved on principle.”

The CSI Effect suggests that the public (and therefore trial outcomes) are affected by the television program and its spin-offs, which wildly exaggerate and glorify forensic science. I extend this to video because the media has so widely celebrated cases in which either video recorded officially by police, or video taken by bystanders, has been used to contradict the testimony of cops who have lied. While laypeople and some police officers can interpret the public's cry for video evidence to support officer testimony to be presumptive societal acceptance that police are liars, there is ample evidence to interpret it in a different way: that officer memory is simply not the best available tool. In the Mississippi Law Journal, Richard Myers argues that the standard of the Terry v. Ohio392 U.S. 1, 30 (1968) rule, of “reasonable and articulable” suspicion, is an incomplete thought.

“Expert police officers,” Myers says, “process much of the critical information on which they rely at a subconscious—and therefore inarticulable—level. The better they get at their job, the less likely they are to make conscious note of classes of information, especially in the potentially life-threatening situations that may lead to frisks for weaponsMyers, Richard, Challenges to Terry for the Twenty-First Century (October 24, 2012). Mississippi Law Journal, Vol. 81, No. 5, 2012; UNC Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2166260..”

As Eric Olson has stated, referring to the way some cops can stand on the side of a highway and select, out of hundreds that are driving by, the car driven by the narcotic smuggler, “That cop probably couldn’t tell you how he knows. But he knows, and this kind of information, which is often so difficult to articulate, is exactly the kind of thing we hope to help analysts articulateSelby, Nick, “Give Me Your Hunches”. Police Led Intelligence. 24 March 2011.”

Olson states:

“Anyone who has gone on a ride-along can tell you that it’s astounding what patrol officers can see – that guy, running behind him? The inspection sticker out-of-date by one month on the car passing the opposite direction, two lanes over? That guy entering the building, who looks as if he doesn’t live in that building? All those kinds of things are examples of something that patrol officers see because they have worked, since the first day they hit the streets under a Field Training Officer, to become finely-tuned anomaly detection devices. If it’s weird, the officer will likely notice it.”

So, according to Myers, “reasonably articulable suspicion,” is really just a subset of “reasonable suspicion based on credible evidence.”

Civilians don't often think through the statement that officers should basically be expected to record whenever they are working, or whenever they are interacting with the public. Generally that's true, but there are some really notable and significant exceptions. The first thing to remember is that, once it is recorded, it is publicly discoverable. This means that, generally speaking, give or take, anything that is recorded can be obtained by John Q. Public through a public records requestWe can debate this, but it's generally the case. In the northeast and in agencies with powerful officer unions, this is a different and perhaps more difficult problem, as laws and collective-bargaining agreements have set precedents in the manner in which officers may be identified, and this issue plays directly to this. This can be highly relevant to the conversation about adoption of body-worn video because it in some cases can create a substantial change in the work environment, which would mean the union would absolutely not be OK with it..

So all that was to get to this: body-worn video is not by any means a punitive measure. And even though officers are granted extraordinary powers in this society, and even though it is right to expect a higher level of monitoring of and transparency into the activities of officers, there must be some recognition of this basic human right to privacy.

Obviously, we don't want video recordings of officers on the toilet. Or officers eating lunch (unless, of course, there's a shooting at lunch, but we'll get in to that in a bit). You can't just (as some have suggested) turn the cameras on at the beginning of the shift and turn them off at the end, because even if the video weren't publicly discoverable, it would be a grotesque invasion of privacy. Not to get too graphic, but who among us wants every symptom, say, of indigestion (or digestion) to be recorded for posterity? Who among us would want recorded every personal telephone call, or every personal in-person conversation?

So, too, are there legitimate reasons why those who come into contact with the police would expect privacy. Consider the reaction of a confidential informer of a body-camera in the room as he describes criminal activities. Think about the battered person describing, on camera, to the police how their spouse or roommate beats them. Or the witness to a murder.

It's important to realize that, while methods and technologies to turn on the camera are going to be developed, things are not as simple as they might appear at first glance.

A new Brennan Center study discusses their findings on policies surrounding the decision about when to record in various large agencies around the country. These policies, as a whole, are rather fascinating to me.</a>

How will the data be shared?

The questions about data storage have not really changed since I last wrote about them, and the question of whether the data must be stored in a CJIS-secured environment has generally been resolved with the general consensus that they do.

Processing and sharing of the data - indexing, mining it, running facial recognition and automated license plate recognition systems against it, audio transcription and other methods of data dissemination will need to be addressed, because the amount of data resulting from a data surveillance state is both useful and terrifying.

I personally believe that the biggest issue we face is the least discussed: retention periods. I will repeat my last post here, because I believe this is the most important.

To put the “How long should law enforcement agencies store video” question into the right frame of reference, I’ll rhetorically ask you this: In a murder or rape case, when should we throw away the DNA evidence?

ACLU’s suggestion on retention policy is that, for a number of thoughtful and laudable reasons, police should measure retention period in weeks, not years. They’re doing this to protect privacy of all, including cops — which is fine in theory but it means that many acts of malfeasance by officers or videos that would demonstrate that an officer was not guilty of behavior of which they are accused would be deleted.

[You can see from a study by The Brennan Center on some large organizations that this is not the way larger agencies are going.]

ACLU’s retention suggestion won’t work for this simple reason: with retention periods measured in weeks, but statutes of limitations measured in years, that will quickly become an intractable problem. Retention will be unlimited, because, as we have seen happen again and again when DNA is used to exonerate people, sometimes decades pass before evidence is needed for the absolutely critical purpose of determining, or proving, innocence.