No Matter What It Shows, Releasing The Video Is The Right Thing To Do

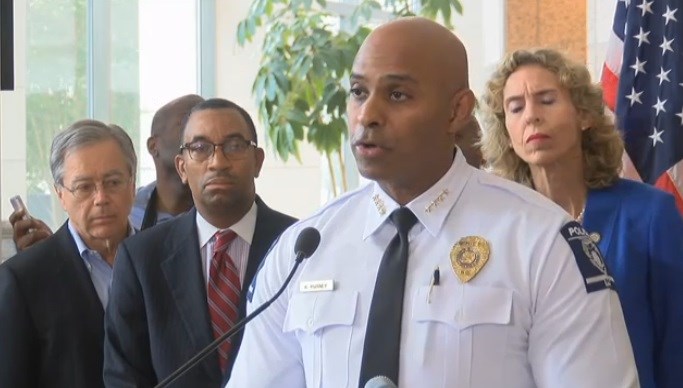

Over the weekend, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Chief Kerr Putney decided to release police video of the officer-involved shooting of Keith Scott. As we saw, the video was inconclusive. It in fact raised many other questions about what happened: why the police fired when they did, and the continuing question of whether Scott had a gun – neither of which was answered by the video.

It is important to recognize that this was likely the reason that Chief Putney didn’t want to release the videos in the first place. That was a terrible mistake. Releasing the videos and all information about the shooting is essential for the community. Releasing the video and other evidence is absolutely essential - even if it leads temporarily to more unrest.

The public used to trust the police to handle these investigations – even though it is true that activists have called for decades for outside investigators, the public accepted that the police were uniquely qualified to investigate these incidents.

Unfortunately, for reasons that are both true and false, the relationship between the police and the communities they serve has in some cases deteriorated. This is inarguable. The police, therefore, must adopt data release policies and strategies designed to demonstrate their trustworthiness.

I applaud Chief Putney, but I maintain he should have done it much, much sooner. He’s not alone: police agencies all around the country need to get more body cameras, make better policies governing their use, and they need to do it now.

The very first key finding from our book, In Context: Understanding Police Killings of Unarmed Civilians spoke as much to the whole country as to Charlotte:

“Law enforcement agencies simply must find better ways to release more data, and to release it earlier,” we said.

“There is a significant public interest in this data, and the public has a legitimate right to understand how it is being policed.

“We call for agencies to release more data, more quickly. In America, we believe that sunlight is the best cure for most challenges between government and the people.

“Police agencies failing to release information look like they’re hiding something, and alternatively, agencies that release what they have, when they have it are invested with the trust of their communities.”

That key finding, to us, was more important than the findings that mental illness and drug use and poverty were better predictors of fatal encounters with police than race, or that there was no defined pattern of systemic bias.

Cops sharing information about officer involved shootings is the single most important thing they must do to keep or earn the trust of their communities.

Withholding the video was a really bad idea.

Ironically, had this event occured next month, the video wouldn’t have been released.

North Carolina House Bill 972, signed into law in July, and taking effect on October 1, changes the rules in the state. From then on, recordings made by police will not be public record. The only people who can see the video without a formal, written request (which sounds like a court order). If the idea is transparency, this is a really crappy way to go about achieving it.

And while Chief Putney has done a good job describing the incident, he is facing an entrenched narrative that contradicts him directly. I personally believe him.

Lots of people don’t.

On Wednesday, I spoke at the International Association of Crime Analyst conference in Louisville and had the conversation about this finding. I mentioned the prime example of how to do it right: Las Vegas.

Vegas had a lot of issues, and when they worked with DOJ one of the best suggestions ever was that they do a brain dump 48 hours after an officer involved shooting: here is everything we know now: names, video, 911 calls, transcripts, interviews…everything.

It was Walter Katz who first told me about Vegas, and when I looked in to it he was exactly right. I’ve spoken with many surprised officers and analysts in Vegas and they all agree: when Vegas started the 48-hour brain-dumps it bought them, over time, the respect of the community and the media, and the trust of both - to the extent that now, when they must say something like, “Oh, sorry, we will release that in a couple of days, we had some challenges,” they are believed, and people do not get upset.

They have established a baseline of trustworthy activity. I spoke with a senior Vegas analyst who told me that has been exactly the case, and that he was really surprised at how effective it has been.

Here’s something else that Walter pointed out – I call it the Katz Condition: Last year there were no indictments of officers in killings of unarmed people unless video was made of the killing. There was only video in 25% of the 153 cases.

Think about that: in every case there was an indictment, there was video. In no case where no video was available was there an indictment.

Now think of Charlotte: we have “inconclusive” video, but a chief insisting that the evidence shows Scott had a gun and not a book. Not releasing video is the department shooting itself in the foot.

I am thankful they have decided to release it. Come what may, it’s better than not releasing it.